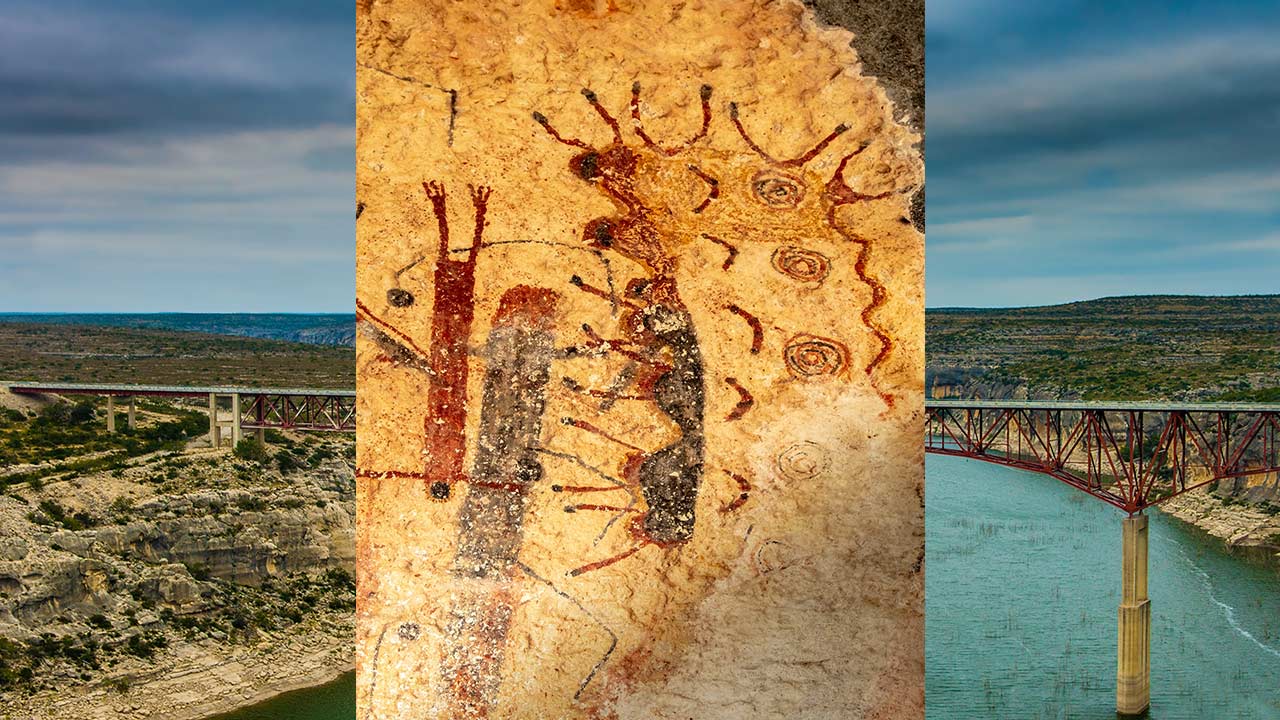

There might not be a more meaningful and unique finding than the White Shaman Mural. Painted on the rock cliff walls high above the Lower Pecos River near Del Rio, this mural has drawn the attention and ponderings of tourists and scientists for many years.

For centuries, Indigenous people roamed, hunted, and gathered throughout Mexico, Texas, and beyond, leaving a rich heritage. Modern-day archaeologists have discovered countless artifacts, including stone tools, mussel shells, and pottery, that have provided insight into what life might have been like for these early inhabitants.

The Witte Museum is a proud guardian of the White Shaman Preserve, a nationally recognized historic site. Accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, it is committed to upholding the highest standards in conserving this invaluable piece of history.

The Creation Story and Ritual Guide

In her book, The White Shaman Mural, released in 2016, Archaeologist Dr. Carolyn E. Boyd suggests that the mural depicts the Huichol creation myth detailing the birth of the sun and peyote.

Boyd theorizes that the mural depicts the story of Indigenous ancestors who lived in a watery underworld that was shrouded in darkness. One day, a group of ancient pilgrims followed a deer that took them on an eastward journey.

The five pilgrims, carrying torches, pursued the deer through the underworld up into the world above. Here, the four-footed mammal slew itself and became the sacred peyote cactus, thus bringing life to the earth.

The White Shaman Mural

Painted on the west-facing wall of a rock shelter upriver from the Pecos River Bridge, the White Shaman Mural is a twenty-six-foot-long collection of pictographs. Its origins date back 2,000 to 2,500 years and was painted by hunter-gatherers from the Lower Pecos canyonlands of SW Texas and Coahuila, Mexico.

The mural received its name after the white human-like figure at the center of the image. A 4,000-year-old form of rock art known as the Pecos River Style predominantly portrays human and animal figures in red, yellow, black, and white.

Over the past half-century, anthropologists and archaeologists have attempted to interpret the mural and its complex imagery. While many beliefs vary, most agree that the images relate to the religious practices and rituals of the native people of the Pecos River Valley.

The Peyote Rituals of the Native Tribes

For many Native Americans, peyote is a sacred plant and a sacrament. Peyotism likely originated north of the Rio Grande in northern Mexico and southern Texas, near the natural northern limits of peyote’s distribution.

Native Americans’ use of peyote was first documented in Mexico in 1560 by Fray Bernardo Sahagún, who mentioned the péyotl root. From pre-Conquest times to the early 19th century, various groups in Mexico and Texas used the peyote cactus.

Peyote use extended far beyond its natural distribution long ago. In the 19th century, it spread northward to Oklahoma, where the Native American Church formalized the modern peyote religion during the 1880s.

In the 20th century, various Native tribes, including the Comanches and Kiowas, traveled to the Lower Pecos region and southern Texas to harvest the cactus buttons for ceremonial use. The Comanches and Kiowas reportedly gathered the succulent along the Rio Grande and Pecos Rivers.

The Four Fountain Springs

Native American hunter-gatherer artists created the incredible murals and pictorial narratives found there as far back as four thousand years ago, transforming the region into a painted landscape.

Gary Perez, a descendant of the Coahuiltecans and researcher, has proposed that the White Shaman Mural serves as both a map of the lands north of the Pecos River and a 4,295-year calendar used to track celestial events.

One of the glyphs in the mural may symbolize the four fountain springs of the Coahuiltecan creation story: Comal Springs, Barton Springs, San Marcos Springs, and San Antonio Springs. Modern Coahuiltecan people continue the traditional annual pilgrimage across Texas, gathering water from each fountain spring as part of their peyote pilgrimage and ritual.

Comal Springs

The Comal Springs, the largest in Texas and the American Southwest, consist of seven major springs and dozens of smaller ones stretching over 4,300 feet at the base of a steep limestone bluff in New Braunfels’ Landa Park. The springs and the Comal River below provide a habitat for the federally endangered Fountain Darter.

The name “Comal,” meaning a flat griddle used for cooking tortillas in Spanish, likely refers to the flat area below the bluff where the springs emerge. The largest and most accessible spring is located just west of Landa Park Drive.

For thousands of years, Native American tribes favored these springs as camping sites, and many archaeologists have discovered artifacts and burial mounds there. In the native language, people called the Comal Springs Conaqueyadesta, which means “where the river has its source.”

Barton Springs

As an Austinite, I find the refreshing cold waters of Barton Springs to be a place of healing and tranquility. Native Americans, dating back centuries, believed them to be as well.

Historians believe the 4,000-year-old White Shaman Mural includes Barton Springs as part of a prehistoric religion’s mystic landscape. Archaeological evidence has revealed traces of the Tonkawa and other Native American tribes who lived around the springs.

In the mini-documentary Spirit Waters, part of Living Springs, Perez explains, “Springs are gateways into the underworld.” The film shows modern-day water ceremonies where women blow smoke into the springs through reeds, allowing their prayers to flow with the life-giving waters.

San Marcos Springs

The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, located on Spring Lake at the headwaters of the San Marcos River, serves as a research and education facility. Spring Lake has been a popular destination for visitors and residents for over 12,000 years.

Many consider the San Marcos Springs sacred. They are believed to be one of the four springs depicted on the White Shaman Mural, representing elements of the Coahuiltecan creation story.

Over the years, the area has undergone significant transformation, and excavations have uncovered incredible artifacts. Discovery Hall at The Meadows Center displays some historical treasures, while Texas State University has digitized several archaeological projects from the area.

San Antonio Springs

The San Antonio Spring, also known as the Blue Hole, is a renowned artesian spring located on the Congregational heritage land of the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word. Indigenous peoples at the time of colonization called the springs Yanaguana, meaning the up-flowing waters of the spirit.

Coahuiltecan Native American creation stories describe how the Spirit Waters rose, giving birth to all Creation. This great spring once surged up to twenty feet into the air. Along with the Comal, San Marcos, and Barton Springs, it is one of Texas’s four fountain springs.

The four springs flow from the vast Edwards Aquifer along the Balcones Escarpment, nourishing rivers that have sustained human communities for thousands of years. This highlights their significance to early civilization.